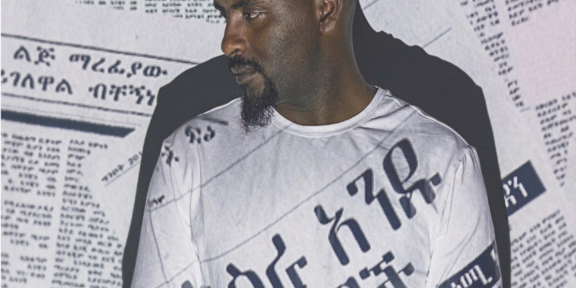

Ibrahim Kassa: Young and Veteran Cinematographer

By Aklile Tsige

Born and raised nearby the village called ‘Bole Denbel’ in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, Ibrahim Kassa earned his diploma in electricity after completing his high school study, and then he has made his dream come true by joining the then Kam Global Film Institute where he obtained his diploma in Film Production, specializing in cinematography.

Moreover, Ibrahim had also the opportunity to get professional training in India. “I was so impressed by everything I was exposed to in India; there are huge film studios as big as cinema halls in Ethiopia. I experienced contemporary editing, cinematography as well as sound mixing and dubbing trainings.” Ibrahim said.

Obviously, Ethiopian cinema has been characterized by its poor sound mixing and dubbing features besides other drawbacks. Ibrahim has gained knowledge and skill on applying a sound mixing and dubbing system called 5.1 surround sound (“five-point one”), which is the common name for surround sound audio systems. 5.1 is the most commonly used layout in home theatres. It uses five full bandwidth channels and one low-frequency effects channel (the “point one”). Dolby Digital, Dolby Pro Logic II, DTS, SDDS, and THX are all common 5.1 systems. 5.1 is also the standard surround sound audio component of digital broadcast and music.

All 5.1 systems use the same speaker channels and configuration, having a front left and right, a center channel, two surround channels (left and right) and the low-frequency effects channel designed for a subwoofer.

Cinematographers and editors in Ethiopia have now begun exerting relentless efforts to update and improve their knowledge and skills in film-making. “Thanks to technology especially the social media like the YouTube we’re trying to cope up with up-dated techniques of capturing motion pictures, and eventually produce appealing movies” noted Ibrahim.

Ibrahim’s exposure to India film-making industry seems to have contributed a bit to the Ethiopian cinema improvement; he has put all his experience in the famous Amharic romantic comedy movie entitled Shefu 1, starring Mahder Assefa, Michael Million and Alemseged Tesfaye. “I think Shefu1 is the first Ethiopian movie made with the application of 5.1 sound system,” he indicated.

He’s highly skilled in studio and location shoots, often collaborating in many languages and cultures, with both large and small crews. He’s worked on numerous feature and documentary films, including Flying Hearts which is roughly translated as ‘berari liboch’, starring the renowned Solomon Bogale and Samson Tadesse. He also produced several music videos for popular Ethiopian singers such as Tsehaye Yohannes, Tadele Roba, Madingo Afework and Tigist Fantahun,

The famous Amharic romantic comedy films he shot, Shefu 1 and Shefu 2, won the hearts and minds of large audience both in the capital and regional towns and has been showing on various movie channels. Ibrahim has played key roles in the making of these movies by directing, shooting and editing.

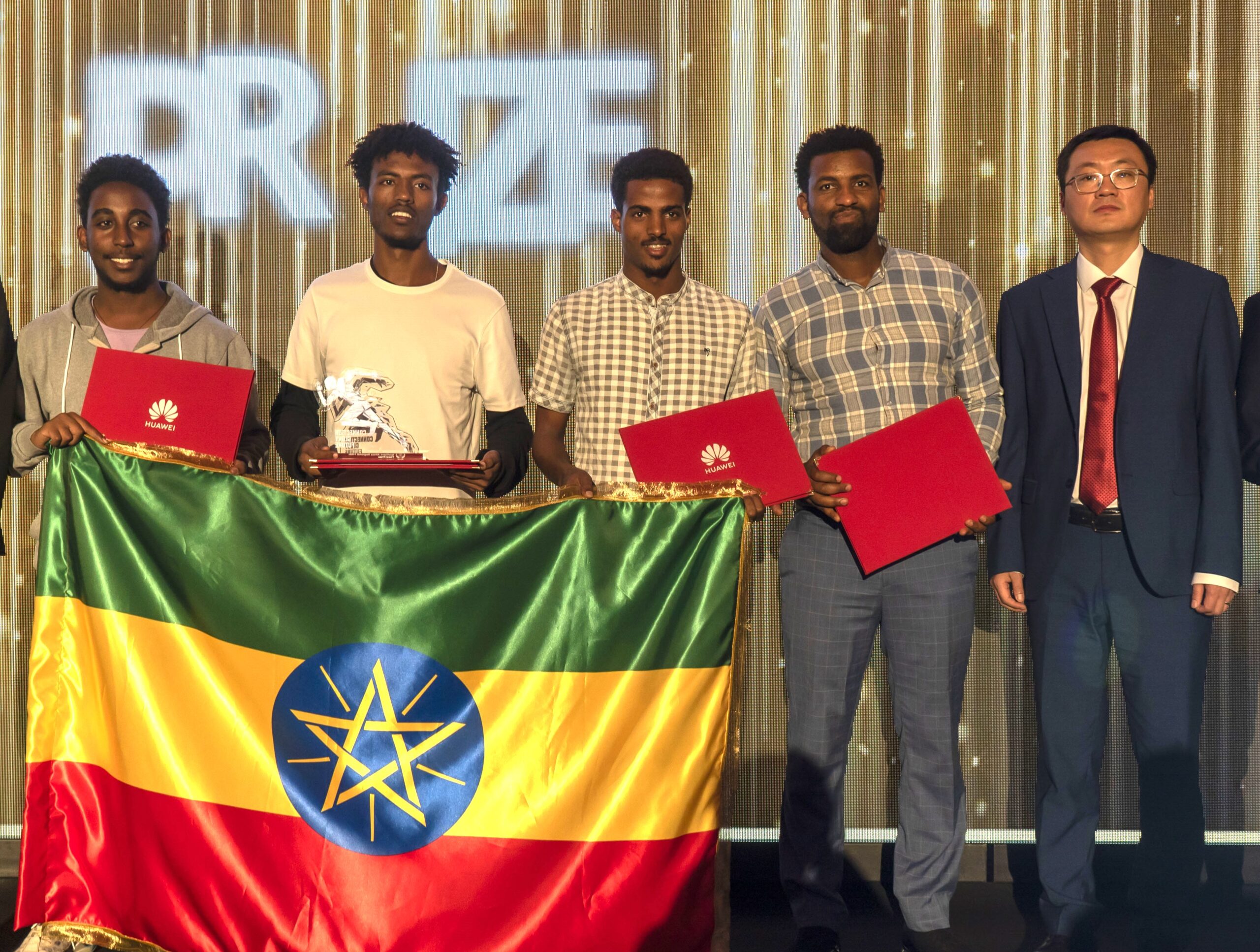

Over the past 17 years Ibrahim has produced over 50 music videos, 40 TV commercials, several documentary films and 16 feature films working as cinematographer, director, producer and editor. For his magnificent contribution to the various audio-visual productions, he has received different awards and certificates, including KAM Global Pictures Best Cinematographer Award and personal present from the legendary artist Merhawi Sitot.

Speaking of the terms “Cinematographer” and “Director of Photography” or DP, Ibrahim described that these two terms are synonymous. It’s the person at the head of the camera department who helps bring the director’s aesthetic vision to life. The DP oversees camera choice (Are we using RED or Alexa? A Sony or Canon or a Blackmagic camera?), lens choice (are we using Canon zoom lenses or Cooke primes?), shooting style (does this scene call for a handheld, cinema verité style or a dreamy, stabilized style using a gimbal? Or a tripod?), and lighting choices.

“…the problem mainly attributes to lack of government’s attention to the sector and lack of training centers across the country. Most of the people engaged in the sector have been working in a very traditional manner, not well-trained and educated due to lack of training schools.”

Often, but not always, the cinematographer fills the role of camera operator because that’s the best way for them to achieve their creative vision, or simply because that’s what the budget allows. On bigger sets, the cinematographer might not even operate camera and they will often have a team under them consisting of a 1st Assistant Camera (1st AC) or a Focus Puller whose job it is to adjust focus on the lens, a 2nd AC who does the clapper board and makes sure the camera has batteries and media at the ready amongst other responsibilities, key grips and electricians are heads of departments that look to the cinematographer for direction, and the list goes on.

According to Ibrahim, a director of photography is often brought onto a project by the producers or on recommendation of the director. The DP is needed early and often in the production process, as he or she is instrumental in deciding on how to interpret the script and make cinematic style and tone decisions. Once thematic styles are fleshed out, the DP will work to put together crews for cameras and lighting.

While the DP may not always do the physical drawing by hand themselves, a cinematographer must still painstakingly go through the film’s script and create visual representations for every individual shot. The storyboard, combined with a thorough shot list, will lay out the film in its entirety so that the director and producers can schedule and plan the production.

A large part of establishing a uniform style for a film revolves around the selection of cameras and lenses for the various scenes. An initial decision needs to be made between digital and film, while taking into account how each would lend itself to a particular look. Along with camera selection, specific lens kits and lenses are hammered out to best capture each shot.

In charge of anywhere from a single gaffer to an entire lighting department, the DP will dictate how he or she wants every scene lit. Lighting setups can vary from elaborate production sets to a single china ball. A great metaphor for the art of lighting compares a cinematographer to a painter, using each layer of light and darkness as a brush to paint a picture within a shot.

Along with the lighting, the DP works with his or her cameraman to properly frame each shot as he or she sees fit. Camera composition can sometimes take hours and requires a pristine attention to detail.

To further complicate lighting and framing, many shots incorporate some level of camera movement to better engage an audience. Basic moves like pans and tilts can be combined with pushes, pedestals, and zooms. This requires a well-orchestrated team to sometimes move lights, dollies, and even collapsible walls to keep up with camera’s view.

Once production is wrapped, a DP can be heavily involved in the post-production process. While not usually a voice on narrative cutting, the DP can work with the colorists and editors to further develop the stage setting.

While directors may get the lion’s share of the glory (or blame) for a film’s critical reception, and producers may get most of the profits, a cinematographer is often the unsung hero of a film’s production. There are some things that can only be communicated and expressed to an audience visually — which can make an impression everlasting, said Ibrahim.

Ibrahim particularly has a strong eye for natural beauty in landscapes, architecture and people. Ibrahim’s work covers a range of styles and disciplines from bright, aspirational lifestyle pieces, to compelling, moody and dramatic scenes. Ibrahim is an expert in every facet of the filmmaking process and is involved in every step of production from pre-pro, to shooting, and through post production. He works with any camera format that is available in Ethiopia.

Ibrahim said that cinematographically Ethiopian cinemas have extremely suffered from poor quality of sound, color, light, shooting angle, editing and some other important film-making elements, adding that every element need to be treated in separate departments.

With regards to the declining of Ethiopian cinema, Ibrahim indicated that the cinema in the country has begun falling over the past few years, mentioning that the problem mainly attributes to lack of government’s attention to the sector and lack of training centers across the country. Most of the people engaged in the sector have been working in a very traditional manner, not well-trained and educated due to lack of training schools.

Putting the Government of Ethiopia as primarily accountable for the falling film sector, Ibrahim recalled that the sector once ranked the 5th item in the nation’s high-income generating or revenue list. However, he said that most of government’s taxation and financial regulations have become bottlenecks for the development of the sector. For example, he said, producers are required to share 50% of their income with cinema hall owners, and to pay a 15% income tax to the government. And 120% taxation has been levied on film-making equipment and materials.

The media houses in the country has also little impact on the development of the sector; they hardly put emphasis on conveying informative, educational and entertaining views and messages on Ethiopian film sector while they allocate plenty of. air time to explain foreign movies and music status.

“Filmmaking is blood and flesh of my life. I am doing it enthusiastically; I don’t think I can live without this profession for I am not doing it only for a living.”

Lack of film-making setting is another barrier to improve the country’s cinema. Both the Government of Ethiopia and the private sector should involve in creating enabling environment for film-making in the country. Artificially constructed scenery needed for filmmaking is so crucial to minimize time and budget allocated for a given film production.

“Many argue that the Ethiopian cinema has gone down since the coming of Kana TV, but I don’t agree with this,” said Ibrahim, and kept on saying, “ Kana TV doesn’t have negative impact on the nation’s cinema development; it’s we, the people engaged in the sector who made the audience stay away from local film screen.”

The film audience was enthusiastic about the coming of local-language films that were closer to their lives and dreams than the Hollywood blockbusters that had little to do with Ethiopian lives and realities. Investors were encouraged to commission many productions simply because filmmaking has become a profitable investment that attracted many talents.

Nevertheless, Ibrahim noted that in addition to the poor cinematographic qualities, most of our films don’t raise strong issues and the story telling has become so silly and good for nothing. This, according to Ibrahim, dispersed the large audience to resort to other alternatives like the Kana TV channel.

In order to alleviate those challenges the Ethiopian cinema has faced the basic principles for filmmaking process need to be implemented by concerned organs, according to Ibrahim. Learning, Making and Repeating are the most important stages to improve film production; producing skilled manpower is the first step to be taken before making the film, and then finally to repeat what has been made with continuous correction of flaws and defects identified in the production process.

Major stakeholders in the sector especially the government should pay critical attention to provide appropriate incentives to producers and professionals by reducing taxation, establishing film academies and implement the already approved national film policy. Furthermore, media across the country should provide coverage to locally produced films and related issues; thereby the country’s film sector would contribute to the national economic growth and development.

Ibrahim reiterated the need to appreciate and acknowledge all local film producers in Ethiopia for their commitment to producing feature films despite their professional qualities, noting that we would not have talked about Ethiopian cinema if they hadn’t made attempts to do so.

According to Ibrahim, most of the Ethiopian films are made by enthusiastic and talented young people who unfortunately lack the real training and professional contacts needed to succeed in the long term and gain international visibility. In most cases, these people learn from trial and error and observation. Though there is an increase in the number of the filmmakers, huge gaps in the basic knowledge are being noticed yet.

Ibrahim appears to be a committed man who puts his heart and soul into everything he does. “Filmmaking is blood and flesh of my life. I am doing it enthusiastically; I don’t think I can live without this profession for I am not doing it only for a living.” Ibrahim noted.

With 17-year of mesmerizing experience in the filmmaking business, he has continued to work as freelance cinematographer for leading audiovisual producing companies, directing, shooting and editing TV commercials, music videos, documentary and feature films.